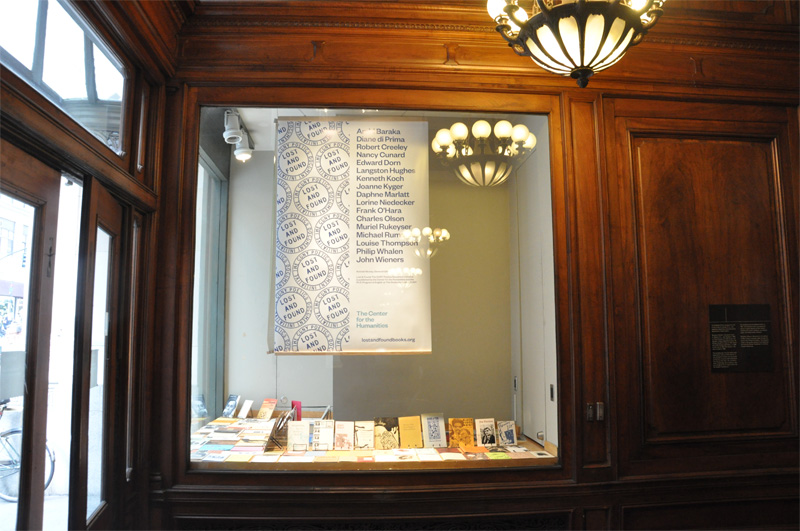

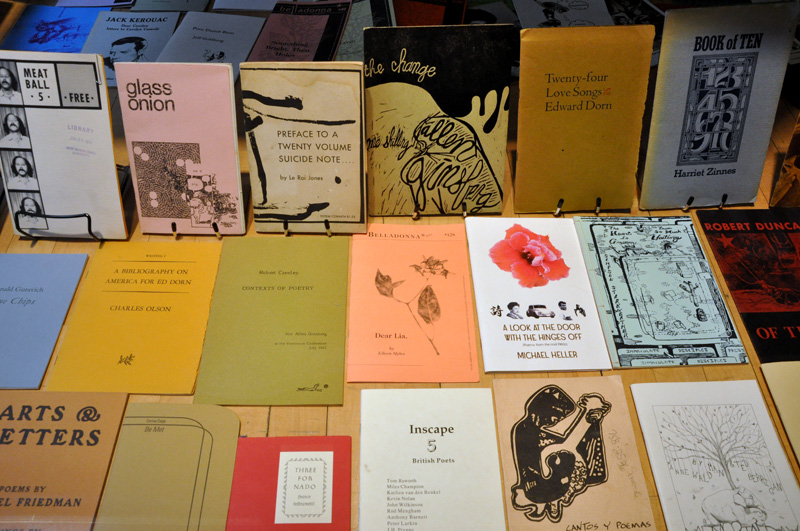

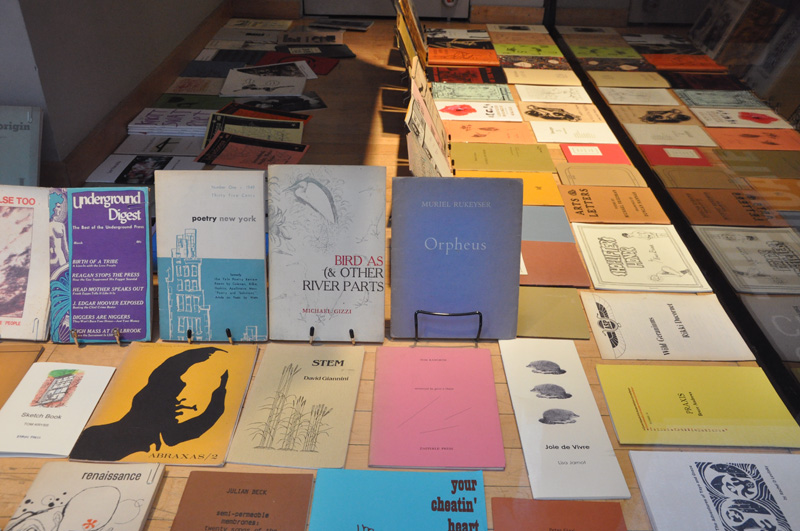

This year we are proud to have Thurston Moore curating the Fifth Avenue window display with a selection from his private collection of rare and underground chapbooks and poetry journals.

For more on Thurston and his collection, read Noise Poetry: An Interview with Thurston Moore by Katie Ingegneri which originally appeared in the literary journal Bombay Gin (issue 38.1, Fall 2011), published by the Jack Kerouac School at Naropa University. You can read the entire interview exclusively on Beatdom in its original form here:

Excerpt from Noise Poetry: An Interview with Thurston Moore by Katie Ingegneri

Thurston Moore …But when I started finding out about the communication between poets through self-published literature, that’s when I became really involved and interested in the history and all the people involved with it. And by the ability to tour across the United States with Sonic Youth, I could go to every college town, and go to the local bookstores – second-hand bookstores – and go into the dusty poetry section and go to the end of the alphabet where they would have the anthologies or whatever, and invariably there would be some boxes of stapled mimeos from the 60s. I began amassing this collection and finding out about the different imprints and different writers that were associated with them, and just seeing all this activity of writing and communication between poets from different regions of the United States.

I was really into learning through investigation, pure investigation. I knew a couple other people who were interested in this stuff, and we would powwow about it, but I didn’t know the writers. So I started going to the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s, when I could, even though I didn’t live in town anymore. And I missed everything – I missed all of Eileen Myles’ running the programs there, being the director there, I missed all of Bernadette Mayer’s era, it was like God, what a fool I was, for missing it. But I just really did not know any better – it’s just this nostalgia for something that I didn’t know existed. But I turned Bernadette Mayer, and Eileen Myles, and Clark Coolidge, and all these people – they became my rock n roll stars, in a way. And it was very private for me. [laughs] So I would go see these people, and I would go up to Clark Coolidge with some of his earlier stapled stuff and have him sign it or whatever, and they’d always look at me like – where’d you get this? Who are you? And I was like, this kid. And some would know who the band was, and they’re just like why is the guy from Sonic Youth asking me to sign this completely obscure publication.

Katie Ingegneri: Now that you have this archive, do you think that will serve a purpose for future generations?

TM: I think it serves a purpose if it’s made accessible in a way that makes sense. I do want it to exist as an accessible library of sorts. I don’t want to let it out of my sight so much because it means a lot to me, but I have talked to a couple of other people who have similar archives and possibly talking to some kind of institution that might establish a library of sorts. But the fact that a lot of the material is so ephemeral, it almost becomes a thing like – do people have to put on white gloves to look at this stuff? I have some stapled mimeo stuff where the edges are crumbling a bit and you really wanna be careful looking at it. So what do you do about that? And there’s some talk about digitizing it all, so it’s all available as digital information, which kind of bores me a little bit. I like the idea cause it makes the work available to read and you can actually see what these pieces look like, but the physicality of the pieces is, to me, very important. So I’m not quite sure how to present it. In a way I feel like all this investigation I’ve done, and the archiving, has come to a really good point because I think a lot of the culture of poetry has become really dependent on the archive as a very real sense of vibrational history. Cause there is all this information, and historical information that’s available, through the Internet, and we can all share this knowledge – but the documentation of it, the actual documentation of it, and what that was physically, and what that meant, has just recently become something of import for a lot of young writers.

In the spring of 2010 I had a show at White Columns gallery [in New York City] where I exhibited a lot of the archive in vitrines and I kind of fetishized a lot of what I liked about it, the visual stimulus of it, and so I made huge posters of about 40 of the covers. And the whole gallery was postered with all these images. There was lots under glass, and I had readings once a week during the show. I had started editing and publishing a poetry journal myself from the year 2000 onwards, called Ecstatic Peace Poetry Journal, cause I had a record label called Ecstatic Peace, and so the show was like a new edition of the poetry journal. And Ecstatic Peace Poetry Journal was certainly all about referencing and wanting to continue the lineage of the aesthetic of this kind of publishing. Which I enjoy doing, to this day. And the idea in my class this week is to actually create one of these journals.

But I don’t really know what to do at this point. I mean, I’m not too concerned about it. I think at some point we’ll figure it out. There’s certain institutions I think that have an awareness of my collection. I know that it’s sort of idiosyncratic, its focus is very personal, so that makes it something else than purely academic. Anne and I were talking about my archive the other night, and she looked at it like “From the Library of Thurston Moore,” that’s its focus, and I was like okay, I like that. I do have everything on file – I keep a FileMaker Pro document of all the poetry – I have to, cause I’ll go into places and find old poetry stuff, and I’ll see these pieces that look so amazing to have been found, and I’ll come home and I’ll look in my FileMaker Pro and see that I have like three other copies of it. [laughs] So I just really don’t know how I’ll utilize it beyond it just being in my house.

But to me it’s artwork, and it sits in my house to me as art, and I’ll figure it out someday. I was actually thinking about weeding it out a little bit and refining it to some degree, and selling off some of it. Which is what I do with records as well – just crystallizing my focus a little more. But I’m not there yet, with that. You know when I think of an archive like Naropa, which is a lot of paper, ephemeral writing, and there’s also this recorded audio, a lot of it on cassette, that needs to digitized or has been digitized. I had come here six years ago and played at a benefit for the school to raise money to allow that archiving to continue. You know, there’s been a lot of relevance attached to the concept of the archive, the archive becomes this really mystical concern or something – which is fine, but it really is just this sort of personalized library, and it brings in this sense of the political where it’s like you’re responsible for your own culture, and recognizing the value of that culture, and what it means in a humanitarian way, what it means in an educational way, what it means in a very emotional way too. So I am okay with it existing contemporaneously as this living archive, we’ll see where it goes.

Read the full interview here: