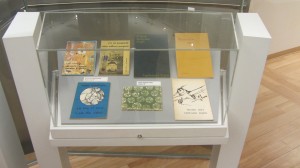

Chapbooks of the Mimeo Revolution: from The New American Poetry

Exhibition: Apr 1 – Apr 12, 2014, Poets House

Reception and Panel: Apr 1, 6-9PM

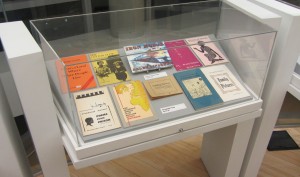

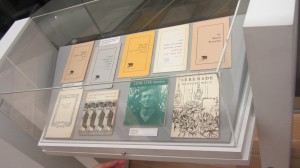

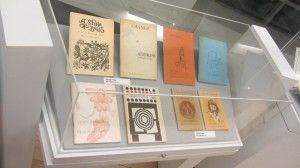

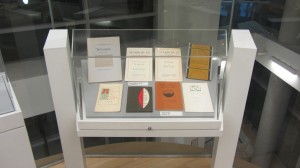

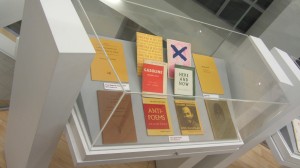

Over the past 25 years, Poets House has amassed the largest open-access collection of rare and out-of-print chapbooks in the United States. In Chapbooks of the Mimeo Revolution: from The New American Poetry to The New Sentence, curators Meira Levinson and Kyle Wuagh highlight the breadth, depth, and richness of the Poets House collection. The chapbooks featured in the exhibition emphasize the geographical dispersal of small presses, as well as the multiform concerns of the work they published. By celebrating the chapbook’s networks of artistic kinship and influence, this exhibit also challenges assumptions about cultural production, transmission and inheritance over the latter half of the 20th century.

To read more about the exhibition, the following introduction has been provided by curators Meira Levinson and Kyle Wuagh.

Chapbooks of the Mimeo Revolution:

from The New American Poetry to The New Sentence

General Introduction

Over the past 25 years, the Poets House has amassed the largest collection of rare and out-of-print chapbooks in the U.S. These handcrafted folios were the beachhead publication of the “mimeo revolution,� a period stretching from the early 1960s through the mid-1980s, during which a multitude of independent small presses sprang up all over the North American continent. At the scattered epicenters of this outbreak of DIY book production were a number of the poets who appeared in Donald Allen’s pioneering 1960 anthology The New American Poetry, and over the next two decades, these poet/publishers fueled a collective transformation of the American avant-garde literary landscape. As the lyrically-driven “organic� forms that characterize much of the work in Allen’s anthology gave way among a younger generation of writers to the more outspoken political work of the Black Arts Movement, for example—published by the Detroit-based Broadside Press—or the formal subversions and radical subjectivities exhibited in the early work of the Language poets—published by the Berkeley-based Tuumba Press—the chapbook remained a generative measure. Its formal limitations proved conducive to reimagining the shape and trajectory of the country during the post-war era, and the medium now embodies the literary-artistic record of that struggle. Highlighting the breadth, depth, and richness of the Poets House collection, the chapbooks featured in this show emphasize the geographical dispersal of these small presses, as well as the multiform geographical concerns of the work they published. By celebrating the chapbook’s networks of artistic kinship and influence, this exhibit also challenges assumptions about cultural production, transmission and inheritance over the latter half of the 20th century.

A Little Chapbook History

Here’s Henry Mills Alden, from his colorful account of “Chapbook Heroes,� published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, v.51, June to November 1890:

No doubt, from a modern book-maker’s point of view, the chapbook

is a squalid, degraded product of a rude, now happily by-gone time.

Truly in itself it presents little or nothing to please either the eye or

the taste; yet, considering it apart from such supersensitiveness, it is

a question whether the study and analysis of this low, humble, obscure

branch of literature might not reward the investigator with very considerable

results, touching upon the manner of thought and intellectual pleasures of

the great lower mass of humanity.

Needless to say, chapbooks are, traditionally, cheap books, trim and portable. The object itself, with progenitors in the broadside and pamphlet, dates back to the introduction of moveable type in Western Europe, but the word “chapbook� (defined by Merriam-Webster as “a small book containing ballads, poems, tales or tracts�) doesn’t enter the language until 1798, the year of Wordworth’s and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads & Other Poems, which reinvented the mode in which many New American poets would operate over a century-and-a-half later.

The Encyclopedia Brittanica tells us that,

most chapbooks were 5½ by 4½ inches (14 by 11cm) in size and were made

up of four pages (or multiples of four), illustrated with woodcuts. They contained

tales of popular heroes, legend and folklore, jests, reports of notorious crimes,

ballads, almanacs, nursery rhymes, school lessons, farces, biblical tales, dream

lore, and other popular matter. The texts were mostly crude and anonymous, but

they formed the major part of secular reading and now serve as a guide to the

manners and morals of their times.

Thus chapbooks were often “news,� of one sort or another, and almost as often apocryphal or pirated, or both—news that took “poetic license,� one might say, news that, as Pound once said of poetry, “stays news.�

Etymologically, “chap� is related to “cheap�—from OE ceap, meaning “trade�—but most agree “chapbook� is specifically derived from “chapman,� the itinerant merchant who peddled like items across Europe, Britain, and North America, from the 16th through the mid-19th century. Hucksters of the “imagined community’s� periphery, these peripatetic emissaries of such “squalid, degraded� products, linked urban centers to their outlying, rural districts. A Chaplinesque, Whitmanic trade, chapmanship was not without its mischief and modest larceny. Sometimes chapmen doubled as petty thieves or highwaymen, a fact underscored by their profession’s affiliation—a multiform binding—with Hermes, the original, nomadic trickster: protector and patron of travellers, merchants, thieves, orators, and poets, and overlord of the in-between, of borderlands and interstices, who freely traverses dimensions, mortal and deific, conveying souls into the afterlife. Stitching a fascicle here, lifting a pocket book there, chapmen knew their way around, were journeymen, on the road, incipient cultural geographers and, like all drifters, strangers, in an eminently Western sense. “The man who doesn’t belong in a community is probably the man to pay attention to,� Edward Dorn writes in his lecture “The Poet, the People, the Spirit,� delivered at the 1965 Berkeley Poetry Conference, which he attended in place (and at the request) of LeRoi Jones, who’d cancelled due to the recent assassination of Malcolm X. The stranger, Dorn concluded, “knows where he’s come from.�

As Alden’s arch positivism makes clear, a number of forces converged in the 19th century to quash the chapbook’s popularity and shrink its circulation (and to stigmatize the stranger as an outlaw, a threat to societal cohesiveness): the mass production of religious tracts, for example, the widespread distribution of inexpensive magazines, the ratification of early copyright legislation and laws curtailing public solicitation and the “hawking of wares,� etc. It wasn’t until the early 20th century, when the hegemonic “center� of the pre-WWI world could no longer hold, that the Dadaists resurrected the chapbook, along with certain leftist political organizations that exploited the medium’s potential as an efficient and inexpensive means for disseminating propaganda. At this point, the chapbook begins its rich 20th century history as an instrument of the avant-garde and an ideological weapon of radicalized class, race, and gender consciousness. It was now a product of and from the outskirts; the current of the chapman’s conduit had been reversed.

The Mimeo Revolution

This exhibit focuses on the chapbook production of roughly a dozen small presses (of the many, many dozens) that sprang up across North America (and beyond) during what has now come to be known as the Mimeo Revolution. Stretching from the early 1960s through the early 1980s, this typographical upheaval gathered energy around members of the Beat movement, as well as former faculty and alumni of the wildly influential North Carolina arts college, Black Mountain, but it soon attracted a much broader spectrum of writers, artists, and amateur printers. “With direct access to mimeograph machines, letterpress, and inexpensive offset,� write Steve Clay and Rodney Phillips, in their indispensible bibliographical history, A Secret Location on the Lower East Side: Adventures in Writing, 1960–1980, this “underground economy of poets� designed, printed, and distributed a massive and vastly diverse body of countercultural, often ephemeral literature that circulated internationally.

At the epicenter of this explosion of DIY book production was Donald Allen’s seminal 1960 anthology The New American Poetry. Allen’s collection had its raison d’être in promoting this expanding, subterranean network of marginal writers, whose work “has shown one common characteristic,� he argues in the book’s introduction: “a total rejection of all those qualities typical of academic verse. […] These poets have already created their own tradition, their own press, and their public.� Many of the poets and publishers whose work is represented in this exhibit are included in Allen’s anthology: Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan, Larry Eigner, Lawrence Ferlinghetti (founder of City Lights Books), Allen Ginsberg, LeRoi Jones/Amiri Baraka (founder of Totem Press), Denise Levertov, Jonathan Williams (founder of The Jargon Society), and the list goes on, comprising seventeen names in all. Even Allen became a publisher, establishing the Four Seasons Foundation (featured in this show) in San Francisco in 1964.

But The New American Poetry’s repudiation of market doxa wasn’t as “total� as Allen made it sound, even if most of the work it included had “appeared only in a few little magazines, as broadsides, pamphlets and limited editions, or circulated in manuscript,� or that a handful of its contributors had spent time in prison (like Gregory Corso or Kirby Doyle). As the short list above suggests, in terms of race and gender, the anthology’s lopsided selection of poets reinforces the base contradictions of its age: of forty-four contributors, LeRoi Jones is the only black person; Helen Adam, Madeline Gleason, Barbara Guest, and Denise Levertov are the only women. At the same time, Allen’s largely regional organization of the book’s content into five sections—e.g., “the New York Poets,� “the San Francisco Renaissance,� the Beats back-and-forth between—betrays geocultural pretensions. Note, in particular, the anthology’s “fifth group [that] has no geographical definition,� Allen writes, but whom he bundles, with strange inconsistency, according to the poets’ origins, specifying San Francisco, New York, and Boston, even Brooklyn and Venice West, and grab-bagging all the rest: “Philip Whalen and Gary Snyder grew up in the Northwest […] Michael McClure came to the West Coast from the Midwest.� Thus, as innovative and generative as Allen’s collection inarguably was, it also set the coordinates of a grid that the dissident constellation and specific contents of this exhibit transgress and reconfigure. Locating a few of the decisive small press interventions that evolved during the initial stages of a still outstanding struggle to overcome the limitations of Allen’s anthology (or any anthology), this show intends to demonstrate the pivotal and equally conflicted role The New American Poetry played in inspiring such challenges to the exclusivity of the milieu it was so instrumental in constructing in the first place. To borrow a metaphor from Whitman, what The New American Poetry made simmer, the Mimeo Revolution brought to a boil.

The anabatic narrative of this show begins at either edge of the North American continent and proceeds to the interior. In terms of chronology, the earliest published chapbooks displayed here (Gregory Corso’s Gasoline, for example, or Denise Levertov’s Here & Now) were published by Lawrence Ferlinghetti’s San Francisco–based City Lights Books, whose publication of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl & Other Poems, in 1956, was arguably the meteor of the post-war Mimeo Revolution. Founded over sixty years ago, Ferlinghetti’s press was essential in situating an entire generation of Beat writers on the national stage, alongside a number of other New American poets, and a long list of international authors, frequently from countries held in contempt of U.S. diplomacy—such as Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Nicanor Parra. While other domestic presses featured in this show reached out to writers overseas—like Burning Deck, or the Great Bear Pamphlets issued by Something Else Press—several presses located abroad are also included: Stan Bevington’s Toronto–based Coach House Press, for example, which published Canadian poets like Bruce Whiteman, alongside American superstars like Allen Ginsberg; the Mexico City–based El Corno Emplumado, founded by Margaret Randall, which published Mexican writers like Sergio Mondragón, alongside American Ethnopoetics pioneer Jerome Rothenberg; and two small British presses—Cape Goliard (founded by poet Tom Raworth, and artist, printer, and filmmaker Barry Hall), and Fulcrum Press (founded by poet and medical student Stuart Montgomery)—both of which published a number of American poets (e.g., Charles Olson, Edward Dorn, and anthropologist Nathaniel Tarn) whose shared imperatives dissect the manifold acculturation of the American West. In addition to highlighting the transnational reach of the Mimeo Revolution, this exhibit also counters the cultural hegemony of the American littoral by spotlighting a number of Midwestern presses, such as Membrane (based in Milwaukee, WI), Toothpaste (based in Iowa City, IA), and Tansy (based in Lawrence, KS)—each of which upended hierarchical designations by juxtaposing the work of local and/or lesser-known authors (e.g. Theodore Enslin, John Moritz, Suzanne Zavrian, etc.), with bona-fide members of the New American scene, like Robert Creeley and Edward Dorn.

Beyond the rhumb lines and blank amplitude of canonical dispensation, this exhibit underscores tectonic shifts in the broader social and political landscape that impressed themselves upon the aesthetic topography of post-war American avant-garde poetics. It reflects the evolution of the Black Arts movement, for instance, from its co-founder LeRoi Jones’ (pre–Black Arts) Lower East Side–based Totem Press, to the aesthetic refinement and anti-conciliatory potency of the chapbooks published by Dudley Randall’s Detroit-based Broadside Press. The exhibit also features three presses founded by women—Diane di Prima’a Poets Press, Margaret Randall’s El Corno Emplumado, and Lyn Hejinian’s Berkeley-based Tuumba Press; and one press—the eclectic and prolific Burning Deck, based in Providence, RI—founded by a married couple, Rosmarie and Keith Waldrop. Meanwhile, the chapbooks of Tuumba and Burning Deck also register the growth of the Language movement—involving writers like Bob Perelman, Carla Harryman, Jackson Mac Low, P. Inman, as well as Rosmarie Waldrop and Lyn Hejinian—which rejected the lyrically driven “organic� forms of the New American poets, in favor of a “new� dis-ideological aesthetic that implicated the reader through formal subversion, and experimented with reflexive and fugitive subjectivities.

But something “organic� obtains in the object, something having to do with its brevity and ephemerality, that not only affords the chapbook an unusual intimacy, but also makes it an attractive vessel for topical and diurnal subjects and methodological approaches. Blurring and recombining generic categories, the chapbook’s unique merger of form and content—encompassing, for example, daybooks and journals (or poems thematizing those forms), anti-war diatribes and “protest� statements, letters, series, studies, sketches, lectures, bibliographies, variations, notes, fragments, and so on—complicates our notions of what constitutes the book as a medium. The 1977 “Year’s End Greeting� from Black Sparrow Press—a holiday card/pamphlet, mailed to subscribers, containing a single a Diane Wakoski poem, “Spending Christmas with the man from Receiving at Sears�—is a prime example of extending and embellishing the discursive and epistolary aspects of the chapbook’s quotidian tradition, as is the freaky lucidity of Michael McClure’s Poisoned Wheat (Coyote Press, 1966), which channels contemporaneous public outrage at the Vietnam War to especially chilling effect, or Jackson Mac Low’s 4 Trains (Burning Deck, 1974), Diane di Prima’s The Kerhonkson Journal 1966 (Oyez, 1971), Tom and Laurie Clark’s Proverbs of the Meadow and the Mountain (Membrane Press, 1986), Ippy Gizzi’s Letters to Pauline (Burning Deck, 1975), Keith Waldrop’s My Nodebook for December (Burning Deck, 1971), and Robert Creeley’s short lecture, The Creative (Black Sparrow Press, 1973). In this way, the modern chapbook thematizes the mobility of its prototype, investing sublunary domestic activities with global dimensions, connecting epochal history to everyday temporalities.

Still, one inevitably becomes familiar with the content of the chapbook only after experiencing its materiality and design—the art, font, paper, binding, texture, and so forth. These elements make the objects unique and memorable, evidenced by the letterpressed debossment of Russell Edson’s With Sincerest Regrets (Burning Deck, 1980), or the Totem/Corinth cover art of Basil King or Black Mountain alumnus Fielding Dawson (cf. Ed Dorn’s Idaho Out), or the masterfully elegant design and typesetting of printers like Graham Mackintosh and Noel Young (see Dawson’s The Yin & Yang Radio Repair Man, or Sanchez’s Native Notes from the Land of Earthquake and Fire). Arranging these chapbooks according to their presses underscores this remarkable achievement in—for lack of a better term—branding. The signature two-tone, angular designs of the covers of the City Lights “Pocket Poets Series,� for instance, are unmistakable, as are the books’ uniform shape and dainty size; one can likewise recognize Tuumba publications by their unique dimensions, as well as the waxy finish of their covers. Just as the authors, printers, and publishers of these books formed lateral, collaborative networks of exchange—long before the MFA perverted writing “communities� into lickspittle sects—founded on personal affinities more than professional associations, and artistic kinship over critical classification, so too their books represent collaborative projects, and radiate the care and close attention that went into their production. It seems almost too obvious to mention that the pleasures of the chapbook as a material artifact are largely lost in the wholesale portage of its content into selected and/or collected hardback tomes, or worse, onto “tablets� or “phones.�

Overall, the chapbook of the Mimeo Revolution was a strategically transient, but home-“made thing,� fittingly opposed, in form and content, to its Simplot/Roundup era—wherein all space became militarized, all time became wartime, and all “problems of the spirit� were subordinated to a single, overwhelming question (as William Faulkner put it to the Nobel committee): “When will I be blown up?� In the midst of this burgeoning, technocratic economy, ephemerality and aesthetic austerity became virtues. No surprise, then, that the psycho-geography to which these post-war writers applied the modernist dictum “make it new,� involved self-consciously situating their work, including its mechanical reproduction, outside, if not against, mainstream concerns. In the chapbook, these poets discovered an empowering and liberating form of marginality that opened fresh networks of correspondence, collaboration, and community, and was evidently well-suited to rethinking the direction and constitution of nation and polis alike, in the long shadow of nuclear holocaust.