This article can also be found by way of our cosponsor, Poetry Society of America, in their .

MC Hyland on DoubleCross Press

MC Hyland is the author of Neveragainland (Lowbrow Press) and the chapbooks Every Night In Magic City (H_NGM_N), Residential, As In ( Blue Hour Press), and (with Kate Lorenz and Friedrich Kerksieck) the hesitancies (Small Fires Press). She runs DoubleCross Press with Jeff Peterson, and is a PhD student at NYU. Visit online.

What is your own personal history with chapbooks? How did they first catch your interest?

I’ve always loved poetry, and loved books as things—in high school, I used to hand-copy my favorite poems into little anthologies for myself and friends. I think I found artist’s books and poetry broadsides first, and then chapbooks through them. I have a very clear memory of seeing broadsides for the first time—fall 1995 at City Book Shop in Philadelphia, where I picked up a broadside by the wonderful Philly poet Leonard Gontarek. And shortly after, I saw handmade books at a student show at the University of the Arts (also in Philly), and I knew that I wanted to do that. Discovering the whole genre of literary chapbooks was like coming home. I can’t remember the first chapbook I fell in love with, but it was sometime in the near-decade between when I started college in 1995 and when I started grad school (for poetry and, eventually, book arts) in 2003. I know that by the early 2000s, I was aware that the poetry world was full of people who had the same object-fetishism I did around books, and was combing the scene for the handmade and the wonderful. As I started to discover the small press world, I was also really influenced by some of the handmade poetry magazines: the never-failing Forklift, Ohio and the happily reincarnated Spork were both revelations, both in form and content.

What made you first decide to start publishing chapbooks?

Well, I made my first chapbook in 2004 while I was a graduate student in book arts and poetry at the University of Alabama. It was a class assignment: I handset a few of my poems in type and made an edition of, I think, 35 books. The first book I made in grad school was easy, though subsequent ones were harder: the program I was in was very fine-press focused, and I found that, working with such precious materials (expensive papers, etc.), I would often get overwhelmed by all the details, all the decisions that needed to be made. A book is a set of decisions: what size you make it, how heavy it is, what the paper feels like, the price—all those things effect the reader’s experience. I found myself struggling on the last one, especially—wanting to find ways to make things that were beautiful and full of care, but that weren’t going to circulate primarily through special collections libraries because I had to charge a whole lot of money to recoup my costs.

So the press didn’t really get going until after I moved to Minneapolis, in the fall of 2008. I had time on my hands: I was house-sitting and really, really underemployed. And I had access to letterpress equipment through the Minnesota Center for Book Arts, where I was a member of the Artist Co-op. When I was in grad school, I’d made a lot of quick-and-dirty broadsides: throwing things together for readings by fellow writing students or visiting writers. I loved the energy and momentum of working quickly: when I made a broadside, it had to be finished by the reading—even if that meant the ink was still wet, and I was cutting them down a half-hour before the reading started. I wanted to make books like that: quickly, fearlessly. And I knew that all you really need to make books is time—if you’re willing to work small, re-purpose materials, and hand-set your type, you can make beautiful things with very, very little financial investment. It seemed like the right time to try—and then I got a bunch of really stunning manuscripts to work with, and I was off and running.

Could you talk a little bit about your own process of making and publishing chapbooks?

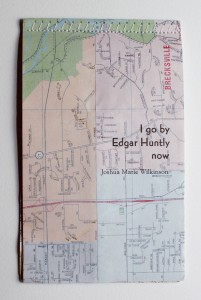

It varies a little from project to project. My first post-grad-school DoubleCross project was what I called the “Single Sheet Series”: books that could be printed all at once, on a single sheet of (usually repurposed) paper, with maybe a separate cover and/or endsheet. It was a way of working with some constraints (which I also love to do as a writer)—and it connected the first set of books I made, all of which were fairly small. Of course, I broke my own constraints—all of the books used at least 2 sheets of paper—but I found the idea of “single sheet-ness” an inspiring way to approach book form: each of the books in the series has a slightly different structure. Matt Henriksen’s Another Word is an accordion fold in a little handmade envelope; Danielle Roderick’s Sextuplets Are Not That Heavy is a classic fold-book structure; Lily Brown’s Museum Armor and Sarah Green’s Hotel Winter are both pamphlet stitches (though Sarah’s book is just a single poem, on a single sheet of paper in a cover); Joshua Marie Wilkinson’s I go by Edgar Huntly now is stab-sewn on a friend’s sewing machine; Brandon Shimoda’s The Grave on the Wall was a Japanese binding (the daifuko-cho—a traditional binding for ledgers—that I learned from master bookbinder Jana Pullman).

Over the process of making that series, I met and started working with Jeff Peterson, who has an incredible eye for cover design—I like thinking about the book materials and shape, and the typography, but Jeff’s the guy for visual punch. We work well together (we’re also a couple: we started dating while collaborating on a book, and are getting married this summer!), and he’s become a really integral part of the process. So we’re yet another one of those couples-run presses now…

Though I’m not as concept-driven in my bookmaking now, I do think it’s important to choose materials and book shapes based on the text itself—or at least, based on a combination of what you have on hand and what feels right for the text. So I make those choices, and then generally Jeff designs the cover, and then we print it together.

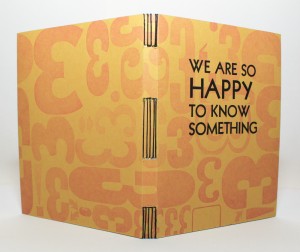

It’s been a while since I’ve made a book that isn’t a simple pamphlet structure, unless you count the handmade poetry magazine I co-edit with Stephanie Anderson, We Are So Happy To Know Something, which is always a little too ambitious, structure-wise. We’ve done three issues, and two of them are this insanely time-consuming hardcover structure, just because I thought it would be cool. Jeff helps out with a lot of the binding, as well, and has become quite the edition binder—there’s a lot of sitcom-watching and gluing/sewing that happens in our household. In terms of running a press, I like the bookmaking and the in-person distribution elements the best: though we have a , most of our sales are in-person, at AWP or the Chapbook Festival or other similar events.

What is unique about the chapbook form, or why chapbooks and not book-books?

Well, “chapbook,” as a term, accounts for a lot of kinds of objects: historical chapbooks, digital chapbooks, things all along the spectrum from an exquisitely detailed handmade thing to a stapled pile of papers to a thin perfect-bound book with glossy covers. For me, the chapbook is about a few things: attention span (mine is short, so I love a book I can read in a sitting or two), distribution (I appreciate the non-Amazon circulation), and editorial taste. Really, I read mostly chapbooks because there are so many chapbook presses whose editors’ taste I think is impeccable. Matt Henriksen (of recently-resuscitated (I hope) Cannibal Books), Jen Tynes (of Horseless Press), Stephanie Anderson (of Projective Industries), JenMarie and Travis MacDonald (of Fact-Simile Editions), Nate Slawson (formerly of Cinematheque Press, and now of New Megaphone), Brian Foley (of Brave Men Press), Guy Pettit & co. (of Flying Object/Factory Hollow Press)—these people are absolutely the ones I want pointing me to new writing.

Do you have recent favorite chapbook from another press?

I have a lot of favorites! I am absolutely smitten with Fact-Simile Editions’ recent One Hundred Colorado Places, by Elizabeth Robinson and Erik Anderson. It’s one of the most beautiful book-objects I’ve ever seen! (In general, I think Fact-Simile’s JenMarie MacDonald is a genius, with her highly conceptual approach to bookmaking.) I’ve also been really digging Kirsten Jorgenson’s lyrical and thought-provoking Accidents of Distance, recently out from Dancing Girl Press. And Projective Industries (my frequent small-press partner-in-crime) just put out an insane and hilarious prose chapbook which brought laughter-tears to my eyes: The Dumbest Question Ever, by a mysterious “PB”—it’s sort of a Nabokovian descent into madness via email exchange over a lost phone charger.